Understanding the functional revolution in front-end applications

Being a front-end developer can be overwhelming at times, and for many reasons: browsers are competing and adopting standards fairly quickly, standards themselves are ever changing and moving fast. But also npm, Github and other tools make it very easy to write your own package / library / framework and to ship it. Therefore, competition is now very fierce and, standards aside, a lot of new ideas and concepts have entered the UI and are spreading quickly.

Today, the main web development trends are about innovations around functional programming. This is why I don't agree much about people calling for a moratorium or a slower pace in "pushing forward". Some technologies we see today could well have been developed many years ago, but at that time some of the paradigms behind them were simply not mainstream enough. Requirements for front-end applications are also a lot more demanding today.

In this jungle, trying to find your way without a map will reduce your chances of success and will increase the likelihood of a burn-out. Instead, it is best to master the basics and understand key concepts about the different paradigms fueling the web. With this article, I hope I will give you, if you need it, a better understanding of functional programming and how it influences front-end applications evolution.

Functional programming at the language level

Functional programming is a style of programming which discourages the use of imperative programming. In practice that means:

- Functions are at the heart of it

- Data mutations should be avoided

It turns out JavaScript has a lot to offer to help you writing your code in a more functional style, mainly because functions are first-class citizens and are treated like any other variable: a function can be easily passed around, return a function, have functions as arguments, etc... And that is one of the key of FP because it makes code composable.

Composability

100% of developers use functional programming at some degree: we all wrap some of our code in functions to avoid repetitions and to help make it more readable. We tend to instinctively break our code in small specialised units that we can use and re-use together: this is called composability.

Let see an example with validating a required string of at least 5 characters: we create a isRequired and a isLongerThan functions, and compose them in a isValid function. All of that without creating additional variables (apart from the functions

themselves) and without using if: use of block statements (if, for, while...) is naturally reduced when using functional programming.

function isRequired(val) {

return val !== undefined && val !== null && val !== '';

}

function isLongerThan(len, val) {

return val.length > len;

}

function isValid(val) {

return isRequired(val) && isLongerThan(5, val);

}

isValid(); // => false

isValid(null); // => false

isValid(''); // => false

isValid('hello'); // => false

isValid('bonjour'); // => true

Purity and high-order functions

There is a bit of jargon around functional programming, below are two important concepts:

- Purity, or pure functions are functions which are free of side-effects and don't mutate their own arguments. Functions which are free of side-effects are functions which don't access external variables or resources to produce their result. This increases predictablility and testability.

- Higher-order functions are functions which take another function as an argument and / or returns a function.

JavaScript is a friendly language for functional programming afficionados. It contains (thanks to ES5) a bunch of higher-order functions which can help write concise code in a functional style.

Let me show you a brief example of a mapReduce operation: it first normalises an array (map), and adds up its values (reduce).

function sumArray(values) {

return values

.map(Number)

.reduce((total, value) => total + value);

}

sumArray([1, '2', '30']); // 33

map and reduce are two well known higher-order functions in FP. What is interesting to notice

is that our initial array is never mutated. sumArray is a pure function which returns a value for any given array.

If at this point you feel you need to learn more about functional programming in JavaScript, I highly recommend mpjme's seires about functional programming. It is straight to the point and funny to watch!

Are functions always functional?

Functions are not always considered functional if they mutate their own arguments, don't return a meaningful result, have side-effects, etc... For instance, JavaScript can have two or more ways of doing the same thing with a functional and non functional way.

It is the case of push and concat. push will add one or more

elements to itself, and then return the new array length. concat will instead return a new array with the added element(s): this

is called immutability. Looking at the code below, it is easy to see which one is the most advantageous.

function push(array, element) {

// Add new element to array

array.push(element);

return element;

}

function concat(array, elements) {

// Create new array with all values

return array.concat(elements);

}

An example with push:

let arr = [1, 2, 3];

let addMore = true;

// Adding elements:

arr.push(4, 5);

if (addMore) {

arr.push(6, 7);

}

// Or the functional way

arr = arr

.concat([4, 5])

.concat(addMore ? [6, 7] : []);

Functional programming at the application level

So far we have talked about FP at the language level. We have seen functional programming can help structuring our code, can make it shorter and will overall make things more predictable and therefore easier to understand and easier to test.

When writing an application, a new dimension appears: time.

Asynchronicity can be hard if not dealt with the right tools. Fortunately for us functional programming can provide them. if you think hard about

it, what is the difference between calling a function a() now or later? There is none, we only need to make sure our functions

are called at the right time: when the arguments we need are available.

There are a few ways to deal with asynchronous code. Callbacks are not an elegant way to do it, mainly because you cannot compose them nicely together unless you use a control flow library. They also don't return a meaningful value, and create so called pyramids of doom.

Instead I will talk about two essential tools of today: promises and streams.

Promises

If you are not familiar with promises, I encourage you reading more about them. In a nutshell, a promise is an object wrapping a future result. It is a nice way to abstract asynchronous operations.

Promises provide functions to help compose asynchronous operations together, some of those functions (.then, .catch)

are higher-order functions. They are well suited to network requests because of their resolved / rejected status, but can be used anywhere else.

Let's say we have a getUserId(name) and a getUserData(id) functions, each contacting a server

and returning a promise. If we have a user name and we want to access its associated data, we will first need to ask for its ID and then its data:

getUserId('thomas')

.then(function(userId) {

return getUserData(userId);

})

.then(function(userData) {

// We have our userData and we can use it!

});

We can also do it for multiple users, in parallel, thanks to .all. .all takes an array of promises and will return a

promise containing an array with all resolved values. In other words, it is mapping promises to their result.

Promise

.all([

getUserId('thomas'),

getUserId('octocat'),

getUserId('red-panda')

])

.then(function(userIds) {

return Promise.all(

userIds.map(id => getUserData(id))

);

})

.then(function(userData) {

let [thomasData, octocatData, redPandaData] = userData;

});

Streams

With streams we enter the world of functional reactive programming.

Streams are simply values published over time. They are basically like arrays with an extra time dimention. They are indefinite in size: when you have an array, all values are available immediately and it has a finite size. With streams it is slightly different: once you open a stream, you can push as many values over time until someone decides to close it. Because we cannot forsee the future, you wouldn't be able to determine the size of a streamed collection. A stream can even be infinite if you decide to never close it!

Streams are observables where a publisher pushes values, and subscribers listen to changes. There are many many stream implementations available: Rx, Bacon.js, Kefir.js, Flyd, Most, Highland... Node.js has also its own implementation, which is used by Gulp.

A common point between all of them? They provide higher-order functions to compose functions over time, and their names are similar to the ones used with arrays:

.map, .concat, .reduce, .merge...

Below is a pseudo-code example of a counter (a click on a button increments a counter):

createStreamFromEvent($('#button').click)

.startWith(0)

.map(() => 1)

.reduce((total, increment) => total + increment);

The created stream will stream the counter value, starting from 0. Each time our button is clicked, a new +1 will be streamed

which will cause a new total value to be streamed.

If you want a good introduction and fly over what FRP is all about, I recommend reading The introduction to Reactive Programming you've been missing by Andre Staltz.

Functional programming at the view level (UI)

So here we are, after talking about functional programming in synchronous and asynchronous situations, let's talk about how this way of thinking can dictate how we build UIs.

First things first, what is a User interface? it is a way to present data and functionalities into something a User can visualize, understand and interact with.

Do you see it coming? a UI can simply be seen as a function of data: ui = f(data). If you pass the exact same data to such a

function, you would expect to get the exact same result.

That is our first box ticked: a UI is predictable.

Components

I could ask the same question: what is a component? But I think you now get it: components are a way to divide a UI into small bits. A component is simply a function

returning a rendered component: rendered_component = f(data).

Components are composed together by having a parent / child relationship. Like in any other GUI, components are organised in a tree. Each component has a parent,

and components can have children and siblings. In the front-end, we traditionally use HTML to describe how elements are organised together. HTML is compiled to

DOM elements (Element objects). A rendered component can consist of one or more DOM elements, depending on how we want to break

down our UI. If we keep following this reasonning, our UI is a component itself made of other components... This is another box ticked: an UI is composable.

If you remember what higher-order functions are, we can also have higher-order components:

- A component taking a component as an argument and wrapping aditional content around it to provide some context. This would be the case of a modal component.

- A component returning another component (i.e. a factory). This would be the case if you want to reuse the functionality of a base component into a new component.

Higher-order components give us more code reusability and increase composability.

Virtual DOM

In practice, having such components would create an under-performing UI which would not scale. This is because DOM operations are expensive and the whole thing wasn't designed for dynamic UIs in the first place.

When we re-render a component, it will always return a new instance of a DOM element (that is the principle of a function, remember!). The old element would then be removed from the tree and the new one would be added. With no existing mechanisms for the DOM to know if those two elements are related, we would have to re-render it completely.

This is why virtual DOM technologies were created: a component is a function creating virtual DOM elements instead of real DOM elements. When a re-rendering occurs, the virtual DOM runs a diff algorithm to create a set of changes to apply to the real DOM (a patch): a new listener to add, an element to remove, some inner text to modify, a class to add, etc...

You can relate this concept to incremental builds or commits in version control systems: only what changes is handled, to limit use of resources available.

Functional programming for front-end applications

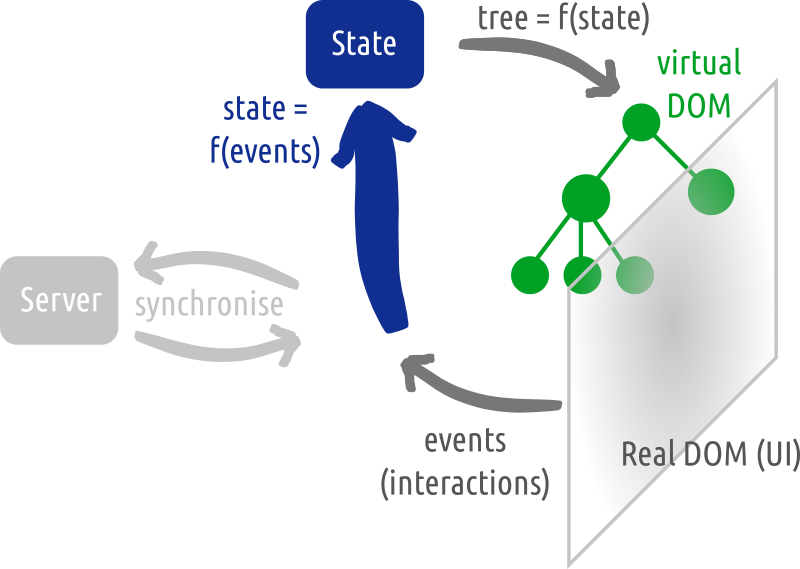

All of this is influencing front-end applications today:

- An application has a state

- This state is rendered in a tree of components, using a Virtual DOM. Data is flowing down the tree.

- The rendered UI will generate events from user interactions which will update the application state.

- Following the state update, the UI will be updated

- The application state can also receive updates from the server

We obtain an unidirectional data flow:

Going further

- A centralised state with nested data (tree) is easier to reason about. It also makes time travel debugging easier, and can be serialised for universal JavaScript applications.

- An application state can be seen as an observable stream too.

- Flux is one way to organise data flow from components to state.

- You can also model users as a function: What if the user was a function? by Andre Staltz

Recommended links

There are tons of resources available online and competing tools / libraries / framework:

- View: React, deku, Om

- State management: Baobab, Redux

- Frameworks, integrated libraries: Elm, Cycle.js

- Router: Router5

- Virtual DOM: virtual-dom, snabbdom

This article was inspired by many sources, one of which is Stay relevant as a programmer.

Something wrong? Fix it on Github!